Just when I’d lost all hope of finding tomatoes with the taste, I remember from my childhood the scientists appear and give us a big surprise. At last they’ve discovered the gene that gives the wild, traditional tomato its taste! I ask myself, how is this possible? And a million questions come to my mind, so I decide to investigate how many types of tomato there are in the world.

Just when I’d lost all hope of finding tomatoes with the taste, I remember from my childhood the scientists appear and give us a big surprise. At last they’ve discovered the gene that gives the wild, traditional tomato its taste! I ask myself, how is this possible? And a million questions come to my mind, so I decide to investigate how many types of tomato there are in the world.

According to the Plant Introduction Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) it alone has made a list of 10,000 different types of tomatoes obtained in the past by farmers around the world. But unfortunately, most, possibly more than 80%, are no longer found in seed banks and there are now few varieties of this tasty fruit that reach the consumer. The reason for this brutal decline is in the standardization of crops promoted in the main by the biotechnology multinationals. Thus, the hybrid tomatoes that are used today for intensive production have a high degree of genetic uniformity.

WOW! It seems that there is a lot here to discuss….

I remember family lunches at the beach in Almería, in my Grandparents’ house, those wonderful tomato salads with a taste and smell that remind me so much of my childhood. One day, without us realizing they just stopped tasting so delicious… we didn’t realize it, but the supermarkets were filled with beautiful looking, shiny tomatoes, perfectly shaped and coloured, but they had robbed us of their natural, wild taste and smell. They had begun to manipulate them genetically so as, according to them, to keep the supermarkets happy but they were wrong. In the end all of us would prefer an uglier tomato, but one which is absolutely delicious. Wouldn’t we?

The origin is still a mystery, but all seems to indicate that the Andes was its birthplace. This has given rise to many arguments because the truth is that there’s no trace of this fruit in the burial offerings, nor are there paintings that reflect the presence of the tomato in daily life. In the indigenous languages of Peru there is not even a specific word for the tomato. This doesn’t mean it didn’t exist, simply that it wasn’t a food eaten by the Incas, but it was merely a wild plant.

It is true that in Peru, there are eight species of wild tomato without genetic variations found in the area that goes from southern Ecuador to northern Chile. Although it appears that it spread through Mesoamerica via the seeds that were carried by the wind, the rivers, the sea and by the birds that fed on these wild tomato seeds, carrying them in their stomachs when they migrated

The first documentation we have on the tomato would seem to be from the chronicles of the Spanish, particularly those of Bernal Díaz del Castillo who told how he and his men were captured in 1538 by some of the native Guatemalans who wanted to eat them in a casserole prepared with salt, chili and tomatoes.

The Aztecs called the Tomato Xitomalt and the southernmost tribes called it Tomati, the name that the Spaniards took, I suppose because of its easy pronunciation or perhaps, as Pepe Iglesias tells us in one of his articles, the explanation can be found in verses from -Tirso de Molina’s work “Love the Doctor”, written back in the early years of the XVII century, during the Inquisition, where he referred to “Salads made from tomatoes with their blushing cheeks, so sweet and yet so fiery”

We have proof of the tomato in the cuisine of the indigenous peoples, thanks to Bernardino de Sahagún (1499-1590) who wrote a “General history about things in New Spain”, where he talks about the markets and the sellers of dishes prepared with tomato: “They sell stews made of peppers and tomatoes, where they usually include peppers, pumpkin seeds, green peppers, plump tomatoes and other things that make tasty stews.

However, according to the rigorous studies of Professor Carlos Azcoytia Luque, Director and biographer of the digital magazine historiacocina.com where I follow so many of his magnificent studies which serve to fuel my enthusiasm and enjoyment. As I said, Azcoytia makes a strong argument that the tomato’s arrival in Europe is not a hundred per cent clear.

Roberto Dodoens, a doctor who was very interested in botany, did dedicate a chapter to the tomato in 1554, considering it very dangerous, comparing it with the mandrake in the Netherlands. It appears that in Europe people were scared to eat it, probably fear of the unknown, so it was used more in medicine and as a decoration.

I could go on giving you an endless stream of data, but for those of you who are interested and would like to delve more deeply into the topic, I recommend that you read the magnificent works of Professor Azcoytia.

Now we know something about its history, let’s return to the taste of tomatoes and their genetic manipulation. Here, once again it must be said that the Spaniards are at the head of the group of researchers with Professor Antonio Granell, at the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology of Plants, a centre of the CSIC and the Polytechnic University of Valencia.

Research published in the journal Science, developed by scientists from the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) of Spain, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the University of Florida and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israel), has analysed 398 varieties of tomato and has found that modern varieties contain less quantity of 13 volatile compounds that are involved in flavour. In addition, they have identified genetic markers that affect those flavour-related compounds.

To understand the problem caused by this loss, Granell explains that the flavour of food doesn’t just depend on our sense of taste, but a combination of taste and smell: “In the tomato, the sugars and the acids activate the taste buds, whilst the volatile compounds, essential for good flavour, stimulate the olfactory receptors”. ”A chemical analysis of this vegetable has detected a significant reduction in the amount of 13 of these compounds, a decrease that is, according to Granell, a consequence of “having maintained, in programmes to improve production, a series of guidelines that are easy to follow, such as colour and size, preserving flavour is more complicated because there are no instruments that can analyse this property, nor is it possible to have a group of tasters selecting the best tasting from amongst thousands of plants. ” However, from now on, this task should be easier. “The molecular markers found can be used in cultivation programmes to grow tastier and more resistant tomatoes”.

To help scientists identify the most appreciated flavours, they had the help of a tasting panel, who were charged with tasting the tomatoes and giving the flavours specific names. The CSIC professor avoids citing the most appreciated, because “it depends on personal taste (there are more than one hundred receptors in the oral mucosa) and cultural”, although he admits that the most valued is the combination of a sweet touch with a balance of acidic and floral and fruity flavours. “The green taste is less appreciated, but it must also be present”.

He also warns: “Not everything is genetics. There are also certain agricultural practices that undermine flavour: overuse of fertilizers or watering the plants frequently, means the tomatoes grow faster but they lose flavour; More limited production means a more intense flavour. Also, remember that traditional tomatoes (those that retain the flavour) “still exist and the seeds are available to those who request them.

One of the latest discoveries that is about to go on the market in the United States is the purple tomato. However, many European governments have much stricter legislation regarding their production, stemming from European restrictions regarding GMO crops.

The purple tomato is a normal tomato to which has been added 2 genes from the Snapdragon flower, a plant found in the rocky areas of the Mediterranean. The plant has high levels of anthocyanins, a very effective antioxidant in cancer prevention, that is also found in berries. The problem with this innovation is the fact that it involves genetic modification, which is why it has generated controversy. We will have to wait and see what happens.

Besides being fresh and tasty, tomatoes are a very healthy food, indispensable on our table. Tomatoes are rich in vitamins C and A. They contain many minerals: phosphorus, iron, calcium, magnesium, manganese, zinc, copper, potassium and sodium. Also, bioflavonoids and lycopene. They have high antioxidant properties. All this makes the tomato very beneficial for our health: Its antioxidants make it an ally in the fight against cancer. It’s good for the sight. It increases our resistance to infections. It prevents heart disease and combats hypertension. It helps aids the muscular and nervous systems to grow. It also has diuretic, anti-inflammatory and healing properties.

As I don’t want to leave without hope, those of you who love the tomato above all else, amongst whom I include myself, the best tomato in the world does exist.

Francisco Ballester and Fernando Sellés are the architects of the rediscovery of this tomato that, after several years dedicated to germinating the old seeds and reproducing this crop, it can now be tasted by the most demanding palates.

These two farmers from Benifaió have already succeeded in harvesting the Cuarentena tomato. The collaboration of farmers, neighbours, cooperatives and experts has been key in the challenge.

It all started in 2008, when the tomato seeds found inside a pumpkin by Vicent Burgés proved to be the Cuarentena variety, a tomato which hadn’t been cultivated for sixty years.

It is great news that the due to the selfless work of many people, we are recovering some of the local varieties which might otherwise have been lost forever.

It’s incredible how products which taste better and have better nutritional properties are disappearing because of pressure from the agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology companies.

Specifically, there are documentaries about the North American giant Monsanto which are hair-raising. But that’s another story.

What I can recommend, whether they are Cuarentena tomatoes or not, is that if they are going to taste like tomatoes it’s important to eat them in season, if not we’re eating those from the greenhouse. Remember the anticipation is also a pleasure! Isn’t this what we used to do?

If you are a city dweller you can still grow your own tomatoes. If you have a balcony, you won’t have a problem, you can even do it in an indoor vegetable plot.

To my mind the best thing I’ve found is this: If you don’t have time or space to personally grow your own vegetable plot, you can rent a working allotment. Several companies offer you the chance to contract a space which will be your allotment or vegetable plot. Here the company will plant your crops, they will tend them and then send them to you when they are ready to eat

Finally, I’ll give you some facts about tomato products and their use in modern cuisine.

In 1812, because of the French influence, the tomato was already being consumed in New Orleans. The tomato’s great opportunity came during the United States’ civil war, where most of the soldiers were boys from the countryside who had never tried this fruit but were able to eat it canned. After the war, they took their new-found taste for tomato back to their farms where it became popular and people began to invent recipes for tomato soups, salads and sauces.

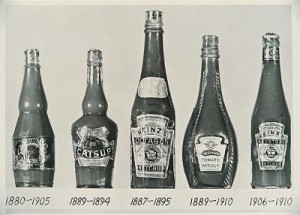

Modern ketchup was invented by the North American Henry J. Heinz, who in 1876 added the Chinese ketsiap to the tomato. Ketsiap was a spicy sauce served with fish and meat, but which didn’t count the tomato amongst its ingredients.

In 1897 José Campbell invented tinned tomato soup. At the beginning of the XX century, tomato was now an important food and started to become an important business in the canning and processing industry. But this aspect deserves its own chapter which we’ll tell another time. For now, let us just say that we’ve reached the end of the story.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.- from electronic sources

¿Cómo conseguir tomates que sepan a tomates?

¿Cuántos tipos de tomate hay?

El mejor tomate del mundo

El tomate morado: ¿mutación o bendición?

Historia del tomate

Historia del tomate

Identifican el gen que da sabor al tomate silvestre y tradicional y que ha perdido el “industrial”