After a great deal of thought, because it’s not an easy task to decide what is the star gastronomic product of the map of Spain, and I’ve opted forMany different types of olives are used in the production of olive oil, depending on the geographical zone and that will determine its sensory properties of taste and smell.

Let’s begin with the origin of the word for oil (aceite)..It’s Arabic, as are the Spanish words for olives and olive trees (aeitunas and acebuches). All of them have Arabic roots. To give an example, aceite (oil) comes from the Arabic az-zait which means juice of the olive.

The story of the Spanish diet is very complex certainly one of the most complex in the world because its geographical position has been a crucial point in the world interchange of foods. It has often been the port of entry of foodstuffs native to Africa and for many of those from Asia which followed commercial routes that finished in the most westerly point of the Mediterranean but above all it was the key link with America, from the time of its discovery products previously unknown on one or the other side of the ocean were interchanged. Products that because of their characteristics had or later developed a universal vocation.

The story of the Spanish diet is very complex certainly one of the most complex in the world because its geographical position has been a crucial point in the world interchange of foods. It has often been the port of entry of foodstuffs native to Africa and for many of those from Asia which followed commercial routes that finished in the most westerly point of the Mediterranean but above all it was the key link with America, from the time of its discovery products previously unknown on one or the other side of the ocean were interchanged. Products that because of their characteristics had or later developed a universal vocation.

Vegetable oils have been routinely used throughout history. They have been used in gastronomy although they have also been employed in other ways, such as religious, cosmetic use and for lighting, being used as the fuel source in the oil lamps that illuminated both everyday life and the temples.

The origin of olive oil production can be found in ancient times in the Fertile Crescent (which extends from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to the Nile).

It is suspected that the first plantations were created in the extensive area from Syria to Canaan. That said, uses of the olive tree are known as far back as the Upper Paleolithic period (12000 AC).

In Egypt, around 2000AC, they began to use olive oil for cosmetic ends. The Egyptians themselves began to commercialize olive oil, importing it from Crete. Inside the funeral chambers we see examples of amphoras and jars of olive oil.

The inhabitants of Greece were already familiar with the olive, but brought from Egypt more widely grown varieties. It is known that olive oil first appeared on the island of Crete, where its cultivation led to its being traded with Egypt and other countries, thus establishing the first trade routes in the Mediterranean sea.

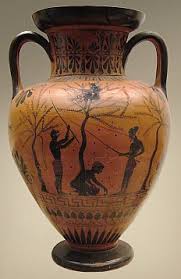

Olives can often be seen in the decorations on vases, in jewellery and other everyday utensils of the period. The consumption of olive oil depended to a large extent on social class, for example the lower social classes didn’t consume olive oil in the kitchen whereas the better off classes did, it’s use as a fuel source for lighting, as a medicinal treatment, as a body oil etc was very common.

In the first Olympic games celebrated in 776 AC the winners of the sporting events were presented with an olive branch as a recognition of their triumph.. At the Panathenaic festivals (similar in importance to the Olympic games) the prizes were amphoras of olive oil (in the so-called Panathenaic amphoras ). The quantity of oil offered as a prize to the winning sportsman could be big, sometimes reaching several tonnes of oil.

In the period of Greek colonial expansion, around the VII century B.C. the Greeks took oil production to Italy. The trade and warring contacts of the Greeks with the Etruscans led to olive growing being introduced into Italy.

The Romans, who were spread all over the peninsula, first discovered the possibility of having a granary, suitable for the production of all cereals but especially wheat, then an excellent oil mill which provided the capital of their Empire with very good oils, above all that of Bética (present day Andalusia) but also from other regions, in such quantities that the vessels of oil when piled up formed a hill which became known as Mount Testaccio.

One of the culinary characteristics of the Roman Empire was their own culinary definition of the barbaric tribes who they deemed incapable of cooking with olive oil and of being therefore consumers of animal fats.

In the Middle Ages, some culinary historians sustain the idea that the fats included in the medieval diet were lower than would appear from the cook books of the time. The northern European peoples included butter in their habitual diet and were unaware of or avoided olive oil, because it was expensive. The contrary one might say to the southern villages. One can see examples of this in the descriptions of recipes given by the Roman Apicius in his book De re coquinaria in which butter is never used as an ingredient. It is true however that butter doesn’t play a preponderant role in Medieval cookery books, such as The Viandier or The Ménagier de Paris. Despite its apparently low consumption in the North of Europe much of the exportation of olive oil from the Mediterranean ports went to Northern cities where they bought olive oil for various uses. However the demand for olive oil fell along with Decadence of the Roman Empire, because the conquering peoples who were from the north disdained the use of an oil which brought to mind the Roman customs of the past. Little by little the state controls of olive oil began to disappear and in the Middle Ages it is the religious orders who take over the reins of production. Consumption among the religious orders who lived in the monasteries and members of the upper classes was always guaranteed.

The use of olive oil during the middle ages was primarily limited to culinary use although it was also used for lighting in the houses and in making soaps and textiles. For these applications olive oil was very useful and difficult to replace. Its medicinal usage in different balsams and medicines is reflected in the medical literature of the period.

The Phoenicians, the great trading nation of the ancient Mediterranean, brought olive cultivation to the Southern coasts of the Iberian Peninsula, present day Andalusia, around the XI century B.C. Quickly the land in question became one of the principal areas where the liquid gold was produced. It was also the Phoenicians who introduced oil production into the Maghreb and Sardinia.

In Roman Hispania (Spain), the province of Bética (in Andalusia) achieved great prosperity due in part to the exportation of olive oil. In ancient times, just as in the present day, the centre of Andalusian production was concentrated in the Guadalquivir valley although in ancient times the weight of production was more westerly than now, when it is primarily in the provinces of Jaen and Cordoba.

The culinary and medicinal use of fats in Al-Ándalus was extremely important and this is reflected in the many recipes which have reached us in the present times. Animal fats such as that of the lamb were being used to aromatize and flavour some dishes. The use of animal fats and it substitution by olive oil was always well received. Olive oil is deemed to be halal, a term commonly used to to describe the foodstuffs considered acceptable under Sharia Law or Islamic Law, therefore its consumption is acceptable within the dietary norms of Islam, this meant that olive oil became very popular during the occupation of the Iberian peninsula.

The Arab peoples who inhabited the peninsula for almost eight hundred years found some very productive olive groves from an economic point of view in the area of present day Andalusia, which had been functioning since the time of the Roman Empire and producing very high yields. This led to the imposition of a single crop system in these areas.

Muslim writers of the time mention olive oil, for example Ibn Zuhr born in the Medieval period (1073-1161) in his Book of Food. This is a text which deals with various topics, it is divided into sections covering different foods which are looked at from a dietary point of view and it does of course talk about olive oil, the different types and its properties.

Olive oil reached the new world with the European colonization of America which occurred around the end of the XV century following the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 under the patronage of the crown of Castile.

As was maybe to be expected this colonization led to the spread of olive oil through the lands of the Americas for the first time ever, given the inexistence of the olive tree in America. It is known that the first production of olive oil took place in the territories of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and that the first growers were Jesuits. The olive tree was one of the first crops that the Spanish introduced into America and during almost a hundred years it spread from California to the South of Chile. It’s use entered little by little into the the culinary traditions of each of the countries of America.

In 1503 the Casa de Contratación (Chamber of Commerce) was founded with the aim of setting the rules for trade with the “New World” citing the products transported by the West Indies fleet, included among these products was olive oil. In the registries of the Casa de Contratación we can read how in 1520 they transported around 250 types of olive trees from the groves around Seville.

Spain possesses the largest olive grove in the world. More than de 300 millions of olive trees covering an area greater than 2.5 million hectares, spread over 34 provinces of Spain, predominantly in the Southern half and the East of the peninsula. This confers enormous economic wealth and is of great value socially, environmentally, culturally and also for public health.

In the last ten years, the average annual production of olive oil has been more than a million tonnes.

After Spain but at quite a distance comes Italy which produces 500 tonnes and Greece with 360 tonnes. Other oil producing countries in the Mediterranean basin are Tunisia, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria and our neighbour Portugal.

Olive oil is a product which has been deeply rooted in our food culture for thousands of years.

Many different types of olives are used in the production of olive oil, depending on the geographical zone and that will determine its sensory properties of taste and smell. The most common is the picual or marteña, native to Jaén and which represent 50% of Spanish production and 20% of world production. It produces a greenish hued oil. Other common varieties are the hojiblanca and the picuda, the base of the oils from Córdoba and Málaga, the arbequina cultivated in Catalonia, the empeltre, which gives the oil of Lower Aragon its characteristic flavour and the cornicabra, a variety typical in Castilla-la Mancha and Extremadura.

Going back to the introduction to this article, any Spaniard resident abroad will be familiar with the process: You go to the supermarket, look in the oils section, you select a bottle of extra-virgin olive oil, notice its Italian label, turn the bottle to look for where it was produced and verify, with a certain degree of shock that the precious liquid was produced in Spain. You turn the bottle once again: Yes, it’s true; the name, the marketing, the image, the brand is Italian.

Spain has and has had for decades a problem of narrative, of how to sell its excellent gastronomic products in foreign markets. Whilst France and Italy have succeeded over the years in placing themselves as premium producers of wine and oil, Spanish companies have only very recently managed to place themselves in the large and highly profitable markets. Why has this happened? There are several answers and also some significant changes of tendencies which suggest that the situation might change in the future. But there’s still along way to go. We are selling more, but we’re selling cheaper. Spain produces high quality oils, but doesn’t commercialize them directly. The most recurrent example is that of the United States. There Italy is the country which leads and by a large margin the market of packaged oil (42% of the total; Spain has 11%) However, Spain leads the bulk market by a large margin (28% of the total, versus the 2% of Italy). North American companies take it on themselves to bottle and commercialize the Spanish oil which reaches its enormous market, but not as Spanish. That being the case, the challenge facing the Spanish producers is to sell the packaged product.

Brand Spain: the narrative which conditions the future and although it has been remodelled in recent years, the disadvantage is immense and it persists. Despite the improvement of its image, Spanish oil is still seen as inferior to Italian and Greek oils due to being positioned as less premium than the oils of these rival countries. The reasons why Italy and Greece are better positioned in the market lies in the late incorporation of Spain onto the international scene. The image of Spanish oil has been at disadvantage historically compared to its Italian and Greek competitors due to the absence of a narrative one which would give Spanish oil a distinctive image in a very competitive arena. This narrative has accompanied all Italian and French products for decades, and is constantly referred to by many businessmen.

This narrative, this “Brand Spain” following the concept that has worked so well in countries around us.

In the long term the aim of the olive oil sector is that whenever a foreign buyer goes to the supermarket they want to consume Spanish products. In many ways they already do so although they are unaware of it. This knowledge, this image placement is the key to the incremental growth of Spanish exports, just as I have discussed earlier in this article.

“Made in Italy”. That’s how the oil exported by Italy reaches the markets, although the only thing Italian about it is the label. Most of the exports are a mix of oils from Morocco, Greece and, above all, Spain.

This illegal practice has led to the association abroad of olive oil with Brand Italy. “The best oil is ours but for many years we have not known how to sell it”.

It’s true that, it’s not only a marketing problem, but also a trade problem. But Italy is our main customer- it accounts for 65% of all Spanish exports- and the second exporter in the world. In other words, it is our main client and also our most direct and unfair competitor.

Italian bad practices are neither new nor unknown, but it’s true that they are increasingly dangerous to Spanish interests.

The Italian traders will continue buying our oil, bottling it, labelling it and selling it as their own. A chain in which once more, Spain loses and Italy wins.

The D.O., is the only leverage of the Spanish enabling them to compete with the exports of countries such as Italy. The D.O. is synonymous with exclusive quality and is only awarded if the oil is bottled from the same cooperative where the olives were picked. A requirement which is not met by most Italian oil.

But, who is going to pay three times more for a Spanish D.O. when one can buy an Italian extra virgin? What the consumers are unaware of is that Italy exports oil labelled virgin extra 100% which contains two thirds of Spanish virgin extra (a variety with perfect flavour and taste, and of no more 0,8 degrees of acidity) and a third of extra virgin Italian oil, which may have defects in in the taste and flavour and as much as two degrees of acidity. This formula when applied to millions of litres clearly supposes a clear competitive advantage for Italian interests.

Well, now that it’s clear that Spanish olive oil is the best in the world, what those consumers, lovers of Premium products must do, is get out there and make sure that when they buy oil, that it is extra-virgin olive oil. You won’t regret it!

To make it easy for worldwide consumers, in February 2016, Olive Oils from Spain the worldwide promotional brand of the Spanish Olive Oil Interprofessional launched in Madrid a new international campaign aimed at reinforcing its leadership in more than 160 countries, focusing on oil from Spain where the highest quality and most consumed olive oils in the world are produced. The Spanish Olive Oil Interprofessional has produced a powerful commercial and an innovative website which functions in 8 languages (Spanish, English, German, French, Portuguese, Russian, Chinese and Japanese) which will be the principal tools used to introduce Spanish olive oil to consumers all over the world.

For those travellers who want to experience at close hand the whole process undergone in producing olive oil, from the olive to the green-hued gold, here are some recommendations for getting acquainted with oil-tourism by visiting historical oil mills:

The Alcabón Oil Mill in Toledo

Just a few kilometres away from the cities of Toledo and Madrid, in Alcabón a town in the province of Toledo, we can find the oldest preserved oil mill in Spain. The mill dates back to the XVI century, although there are some studies which date the machinery to as far back as the VIII century, and it’s located in an XVIII century construction where we also find the oil press. The oil mill is situated in front of the town hall, in a building which was remodelled in 2007, and became the Museum of the Alcabón Oil Mill, also serving as a bar-restaurant.

Guided tours of the premises are available.

Cafeteria and restaurant services available.

Contact Details:

Alcabón (Toledo)

Tel.: 925 77 96 31

The Old Oil Mill of Sierro in Almería

Sierro oil mill, has played a fundamental role in the livelihood of the village, mostly made up of agricultural workers, and where the difficult topography of the township, made bartering a way of life amongst its inhabitants in a place which is geographically isolated and strictly rural. The emblematic oil mill of Sierro closed its doors permanently at the beginning of the nineties today however it is once again full of life,this time, converted into the Mesón Pan y Aceite (the House of Oil and Bread). The restoration by the town’s vocational training centre has preserved the essence of the building it has the original machinery is identical in appearance to the original. It is located close to the River Sierro, in a landscape of extraordinary natural beauty, part of the Sierra de los Filabres. The Sierro oil mill is also an ethnological museum which is open to the public, where one can learn how the olive was converted into the prized golden liquid in a time when in the country, mules were man’s greatest allies. The Mayor of Sierro, Juan Rubio, stresses how the oil of Sierro has always been of an excellent quality. The representative of the Sierro council has invited the inhabitants of the Valley of Almanzora and the region to come and discover hi village and especially in this new phase, the old oil mill with the certainty that nobody can fail to be impressed.

Contact details:

Mesón Pan y Aceite

Calle Padre Pepe (unnumbered). Sierro (Almería)

Contact: Miguel.

Telephone: 950107945 – 656681663

Email: mesonpanyaceite@gmail.com

An oil mill forgotten by time in Ceclavín in Cáceres

Looking for Oil-tourism options in Spain to offer you, we have found this gem, forgotten by time situated in Ceclavín, a town in the province of Caceres: We know from the Catastro de Ensenada (a large scale census carried out in 1749) that in the XVIII there were in our township 4 oil mills which were moved by teams of horses. The Catastro tells us the names of the owners and the there locations (streets in the village) and although we have searched hard, all that remains of their presence are some scattered rollers (conical stones). A forgotten oil mill. About 6 km. from the town if we take the road of the Camino de la aceña de la Orden, and then the road which leads us to the sitio de los infiernos, close to the river Alagón, we can find two semi-ruined buildings, surrounded by olive trees. The first building housed the Oil mill itself, the second building was used to house the workers of the mill.

Oil Mill and Museum of Traditional Agriculture in Granada

The Museum of Traditional Agriculture and Oil Mill in Granada lies at the foot of the Zahor hill, perched on the edge of the cliffs of the River Torrente in Nigüelas. Its location means it has splendid panoramic views of practically all the Alpujarra region. The Oil Mill and Museum of Traditional Agriculture is housed in a Nasrid building constructed between the XII and XIV centuries and houses one of the oldest oil mills in Spain.

Address : C/ Canalón 12 E – 18657 Nigüelas

Telephone : 958 77 76 07

An oil mill in the House of Dulcinea Museum in El Toboso in La Mancha – Toledo

This is housed in a building which still conserves part of its original XVI century structure and despite the passage of time and the various alterations it has undergone over the years it still preserves in general terms…the characteristics of a Manchegan gentleman’s house with its various outbuildings: mill, wine cellars, patios, animal pens, wells, etc….This house belonged to one of the most distinguished families of El Toboso, the Martínez Zarco de Morales, whose coat of arms may be seen on the front of the building. Tradition has it that in the time of Cervantes it was the residence of Don Esteban and his sister, Doña Ana, who was the inspiration for the peerless Dulcinea of El Toboso in Cervantes’ famous work, “Don Quijote de la Mancha”. This tradition is part of the patrimony preserved by this museum. Access to the house and the museum itself is via a hallway which leads to the service areas at the rear of the house, the kitchen, the pantry, the courtyards and the animal pens and amongst them we find an oil mill, a grape press and a dovecote.

Contact Details:

Museo Casa de Dulcinea. C/ Quijote, 1. 45820 – El Toboso (Toledo)

Group visits: By previous appointment.

Telephone: 925 197 288

El Toboso Tourist Office. C/ Daoíz y Velarde, 3. Tel: 925 568 226

Goicoechea Mill in Zaragoza

This mill was constructed by Juan Martín de Goicoechea, businessman and dignitary based in Zaragoza who had previously worked in the textile industry… which he abandoned not seeing a great future for it in Aragón. So after a few years of doubting (1779-85) he decided to take advantage of the site of a silk mill which he owned to construct an oil mill with six presses.

source: “The Goicoechea and their interest in land and water in XVIII Aragón”. Zaragoza, 1989

Oil Museum in Santa Cruz del Valle in Ávila

This museum is located in the old Oil Mill of Santa Cruz del Valle in the province of Ávila in the beautiful scenery of the Valley of the Tiétar. It has been restored; in the first phase they carried out the restoration work on the oil mill, and in the second phase they did further work such as installing air-conditioning and putting up shelves to hold examples of extra virgin olive oil from the Mediterranean countries. They hope these will hold around 3,000 bottles, making it the first classified oil collection, not only in Spain but in the world. A former worker at the Oil Mill when it was still operational will show you around the museum, taking you through all the steps from the olive to the oil.

Contact Details:

It can be visited from Monday to Friday, except Wednesdays from 19.00 to 21.00.

Address: Plaza De la Constitución, 1, 05413 Ayuntamiento de Santa Cruz del Valle, Ávila,

Telephone:920 38 62 01

The Jaganta Oil Mill in Teruel

The oil press, or oil mill of Jaganta can be found in the neighbourhood of the same name, within the town of Las Parras de Castellote. The building which houses the oil mill is a simple, traditional mud construction covered by a single sloping roof made of wood, thatch and tile, it has two entrances to facilitate the coming and going of the animals laden with olives. In the main entrance, a small pool which functions as a water source is used to supply the mill with water. The machinery added at the beginning of the XX century has also been conserved. This mill ceased working a few years after the Civil War, beginning its revival from around 1994-1995.

Contact Details:

Address: Jaganta, a neighbourhood of Las Parras de Castellote.

Region: Lower Aragon

Guided tours by prior appointment

Contact persons : Grupo de Estudios Masinos

Tels. 978723072/978848807/679522072. Parque Cultural del Maestrazgo: 978849713

If you’re one of those people who want it NOW! But you live outside Spain, I’ll give you some digital platforms which act as a bridge between the producers who don’t have their own online store and the foreign tables and kitchens. It’s a way of selling Spain to foreigners via internet. If the ingredients which make up the Mediterranean diet are appreciated beyond our borders, why not offer you the opportunity to enjoy them in your home?

La plataforma ofrece desde 2012 los artículos oleícolas de cualquier productor que, de manera gratuita, quiera inscribirse. Está pensada como un ‘link’ desde el origen al consumidor final, quitando intermediarios. Fincalink ya cuenta con 20 productores, y sus clientes son en su mayoría particulares. Cuando hay un encargo, Asensio avisa para que preparen el envío y gestiona la logística. De momento, solo exporta a Europa, principalmente a Reino Unido, de donde provienen muchas de las ventas.

otra plataforma que vende aceite de pequeñas cooperativas cordobesas. Junto con el pedido, envían a sus clientes un certificado de que el líquido se produce y envasa en el mismo sitio (incluso pueden conocer la parcela exacta donde estaban los olivos), y de que se trata de aceite virgen extra.

Los aceites de oliva virgen extra que se producen, comercializan y exportan en ILOVEACEITE® proceden exclusivamente de olivos cuya producción están situados en Peal de Becerro (Jaén) y tienen su origen y calidad amparados por la Denominación de Origen «Sierra de Cazorla». Exportar nuestro aceite de oliva virgen extra a todos los rincones del mundo es uno de nuestros principales objetivos. Eficacia, solvencia, garantía y calidad en los productos, nos han permitido exportar a países como China, Ghana, Honduras, Paraguay, Ucrania, República Dominicana, Perú, India, Polonia, Bélgica, Japón, Sudáfrica, Francia, Alemania, Austria, Irlanda entre otros.

Oliva Oliva es el mayor portal de venta de aceite de oliva virgen extra en Internet, con cerca de 300 productos online, e incorporando cada día nuevos productos seleccionados. En Oliva Oliva, el cliente compra el aceite de oliva virgen extra directamente a la almazara productora, al mismo precio de venta que en la almazara. El producto se recoge, por tanto, en la almazara de origen, recién envasado y empaquetado por el productor, expresamente para el comprador de Oliva Oliva. El cliente puede probar distintos aceites, en pequeños formatos, antes de realizar un pedido a la almazara. Para ello puede elegir entre los mejores aceites que se encuentran en la página “Selección tienda”, los cuales se pueden adquirir por unidades sueltas, y con un solo gasto de envío para el total del pedido.

La Tienda, productos españoles en EEUU. Williamsburg (EEUU), allí es donde Don Harris fundó la empresa de pedidos por Internet de productos tradicionales y auténticos alimentos gourmets españoles, de nombre “La Tienda“, hace ahora diez años. La empresa se fundó con el objetivo de proporcionar a los españoles con morriña algunos productos tradicionales de su tierra, sin embargo, el negocio fue más allá de los españoles y convenció también a los residentes americanos de consumir autenticas delicias españolas. Don Harris, conoció España cuando su buque tocó puerto español en 1965, siendo joven capellán de U.S. Navy. En 1973, y mientras crecía la familia, residimos cerca de las bodegas de vino de jerez en el casco antiguo del El Puerto de Santa María (Cádiz) durante nuestro destino en la Base Naval de Rota. El aprecio que sentimos por esta forma de vida tan cercana en la que los lazos familiares son primordiales, en la que los niños son mimados por todos, y en la que las diferentes generaciones cotidianamente se reúnen y conviven mientras que disfrutan de una comida sana, fue en aumento al compartir nuestro día a día con vecinos españoles. Ahora, diez años más tarde, La Tienda cuenta con más de 650 productos, la mayoría de ellos de alimentación, y algunos de cocina y de mesa, y más de 50.000 clientes. A través de su página Web y en su establecimiento, la empresa vende más productos españoles que cualquier otra en Estados Unidos.

Aceites García de la Cruz 1872

La evolución de la alimentación y la gastronomía en España

Monte Testaccio: Cuando el aceite español creó una colina – por SIBYLA el 29 de sep de

2014 Fuente: Estudios sobre el Monte Testaccio de Blázquez y Remesal

Esencia de Olivo: cultura del Aceite de oliva virgen extra

España, primer productor mundial de aceite de oliva

Magnet

España, el líder mundial de vino y aceite al que nadie quiere comprar fuera

La ‘marca Italia’ se queda con el aceite español

Almazaras Historicas

Vino, aceite de oliva y otras hierbas: vendiendo España al extranjero a través de internet